From parish pauper to plough boy

A 1905 newspaper report throws new light on the shepherd's childhood

Nothing can prepare you for the thrill of discovery – the exhilaration and joy of encountering your first significant breakthrough in a local history project. It’s inevitably only when you are searching for another specific piece of information that something else is thrown up, which is completely unrelated, but so much more important than you could ever have imagined!

Last weekend, I cried out at my laptop screen in disbelief when an online search in The British Newspaper Archive threw up tens of articles referencing Richard Widdows – from the local and national press. I was stunned by the sheer number and amount of interest from across the country, and even as far as Canada! After a closer read of these press cuttings, though, it was apparent most were limited to a few lines on an inside page, imparting little information. They regurgitated similar copy, focused on Widdows’ great age. They relayed the King’s message of congratulations on Widdows’ ‘102nd’ birthday and subsequent birthday celebrations. The same messages were rolled out: how remarkable it was that Widdows could shave unaided, tend his garden, smoke his pipe and even go for a ride on a motorbike at the age of 103!

However, when I entered Withers (aka Widdows) in the search for the Oxford Weekly News, I uncovered a series of significant revelations in a single article. A piece published on 11 October 1905, ‘A Great Rollright Centenarian: sketch of his career’, which reported his reminiscences. It was as if I was hearing Widdows’ voice for the first time. What is more, it filled a sizeable gap in his biography, which I had assumed would remain a blank forever, by telling the story of his childhood: where he spent it, who his parents were and how he came to Rollright.

The article recounts that Widdows was born in Burmington, near Shipston-on-Stour. His father was a ‘Great Rollright man and a soldier’.

Widdows recollects the celebrations marking the battle of Waterloo in 1815, when he would have been no more than 4 or 5: ‘when the news of the defeat of the French arrived at Burmington … an effigy of Napoleon’ was ‘carried around the village on a donkey’.

However, family life in Burmington must have been brief. For his father: ‘Not being fond of his profession, he deserted as many as three times. When he was retaken (and this occasion Mr. Withers well recalls), he was in the “condemned regiment,” or in other words the “forlorn hope,” and was not heard of again by his son. Mrs Withers married again and went away to Exeter.’

Abandoned by both his parents, Richard and a younger brother were left to ‘the mercy of the parishioners. They spent their infancy in the institution which in those days took the place of the present workhouse.’

Widdows does not mention where this institution was located. Burmington was too small a parish to have supported a workhouse: hardly more than a hamlet, its population hovered at over 100. Shipston-on-Stour, a couple of miles away, had a workhouse housing 30 people in 1776. After the Poor Law Act of 1834, a much bigger workhouse was built there, the Shipston on Stour Poor Law Union, that accommodated the poor from parishes across Warwickshire and Worcestershire.

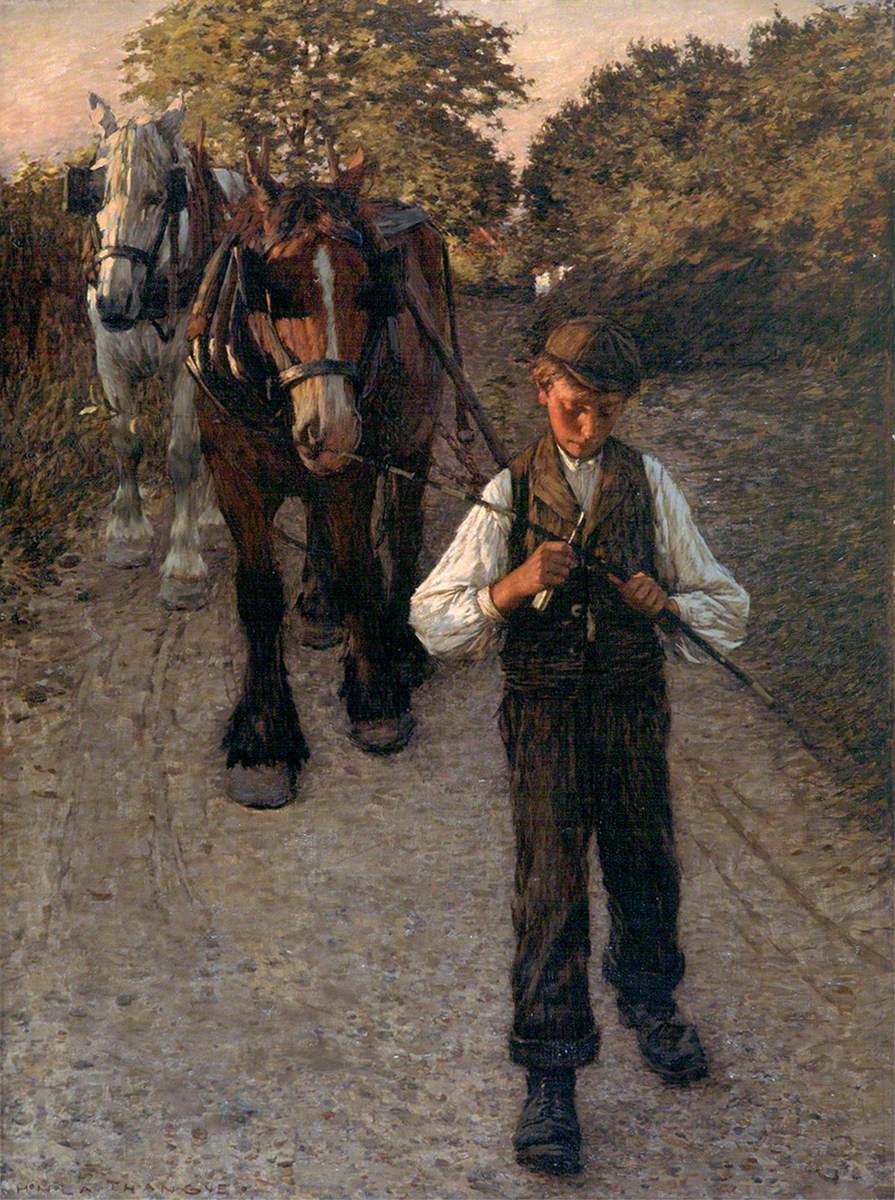

The parish didn’t support abandoned children, though, for long. By ‘the age of 10 or 11 Richard commenced to work for his living, and being big enough to drive the plough went to work at Coombe Farm’. This move to a farm in Great Rollright goes unexplained, but it seems likely that it was connected to his father’s roots in the village. In the 1820s, Coombe Farm was farmed by tenant farmer Thomas Harbidge and his family. A restless adolescent, Widdows didn’t remain in Great Rollright for long:

‘Soon after this he decided to seek his fortune further afield, and went with some other youths to Birmingham. But things did not turn out as they anticipated, and he returned to Great Rollright, and again found employment at the farm where, in the capacity of a shepherd, he remained for 50 years for the greater portion of this long period working for the late Mr Fletcher.’

The settled existence that Widdows lived for the rest of his life in Great Rollright contrasts with the turmoil of his early years. The reports of him as ‘a centenarian’, all emphasise his modesty and appreciation. Supported by the parish of Great Rollright before the state pension was introduced by Lloyd George in 1908, in his very final years, the fear of the workhouse must have loomed large after his childhood experience.

That must have been such an astonishing moment, to discover so much more than you'd imagined... it's amazing that after all that turmoil in his youth that he found a settled life again and became so celebrated too. Amazing to hear his voice...