How many of us will have our occupation written on our gravestone? Richard Widdows did. ‘Shepherd’ appears in brackets immediately after his name on his headstone in St Andrew’s churchyard, Great Rollright. By the time of his death in 1910, his identity had become synonymous with that of a shepherd. In this professional photograph, taken towards the end of his life, he is posed with a crook and a mangy dog with a matted coat, who looks as if he has spent time in muddy fields!

For Widdows being a shepherd must have been more than a job, it was also a matter of pride. James Rebanks perfectly captures the respect that a ‘good shepherd’ gains from their work when writing about his grandparents’ generation in his book The Shepherd’s Life: A Tale of the Lake District (2015):

‘Men or women who were good shepherds were held in the highest esteem, regardless of being to modern eyes “just employees”. To be a good shepherd was to stand tall as any man.’

From agricultural labourer to good shepherd

Widdows worked for about three decades as an agricultural labourer before he gave his occupation as ‘shepherd’ in the 1861 census (In 1841 and 1851, it was entered as ‘agricultural labourer’). He was 50 years old.

Widdows was not alone. In the 1861 census returns for Great Rollright, 8 individuals entered their occupation for the first and only time as shepherd. (In 1871 Widdows reverted to entering ‘agricultural labourer’, only returning ‘retired shepherd’ in 1901.)

So, what changed in 1861 in Great Rollright? As Mark Page notes in his paper on the economic history of the village for VCH History: ‘Until the 20th century Great Rollright was a typical Cotswold farming village, combining traditional sheep-and-corn husbandry with cattle rearing and dairying.’ It seems that the balance tipped in 1861 from mixed farming that was predominantly arable towards sheep, only to shift back again from sheep in the 1870s and 1880s.

As described by Andrew Copus in ‘Changing Markets and the Development of Sheep Breeds in Southern England 1750-1900' (Agricultural History Review, 1989) the market for short staple wool peaked in the 1860s. Areas, such as ‘the stonebrash hills of Oxfordshire’, also benefited in this period from a new breed of sheep – the Oxford Down – a cross breed between the Hampshire Down and the Improved Cotswold: ‘The new breed retained the large size of the Gloucestershire sheep, without sacrificing the hardiness, early maturity, and quality of meat and fleece of the Hampshire Down.’ By the onset of the agricultural depression in the 1870s, the fall in prices of arable products and the increased cost of labour ‘resulted in a fall in sheep numbers in all the sheep-corn and transitional districts’.

By the end of the 19th century, Page describes how in Great Rollright ‘an increased emphasis on dairying prompted a modest rise in cattle numbers and a fall in those of sheep’. Though it ‘relied chiefly on the sale of store cattle and milk’, Manor Farm, one of the biggest estates in the village, retained ‘a “splendid flock” of Oxford Down ewes’.

The good shepherd and the hireling

It is difficult to gauge how much sheep husbandry Widdows would have undertaken throughout his working life on mixed farms, as an agricultural labourer and shepherd. He may even have grown up around sheep in Burmington, close to Shipston-on-Stour, which is well-known as a wool town. He would, though, have been very much alive to the regard that shepherds are held in, in contrast to labourers. As a regular church goer, he would have been intimately familiar with the parable of Christ ‘the good shepherd’ (John 10:11-18) in which ‘the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep. But he that is an hireling, and not the shepherd, whose own the sheep are not, seeth the wolf coming, and leaveth the sheep, and fleeth: and the wolf catcheth them, and scattereth the sheep. The hireling fleeth, because he is an hireling, and careth not for the sheep.’

There were financial as well as social and cultural benefits to being defined as a shepherd rather than a labourer. This is spelled out by GE Mingay in Rural Life in Victorian England (Alan Sutton Publishing, 1976): ‘In Dorset, according to the Royal Commission Report on Labour of 1893-4, ordinary Labourites were earning near the end of the century 10s a week, and carters, shepherds and cow men from 11s to 13s. … Shepherds received extra payments of 1d for each lamb reared (6d for twins), and 13d for twins), and 12s or 13s for every 100 sheep sheared.’

The romanticisation of the shepherd

The popular rise of the shepherd in European art and literature coincided with the Great Agricultural Depression (1873–1896), which was triggered by the cheap importation of grain from the American prairies and Russia. The drop in English corn prices was exacerbated in the 1870s by atrocious weather conditions and poor harvests. As farmers struggled, there was also an acceleration in rural depopulation with labourers moving to towns and cities for better paid work. The Dutch painter Anton Mauve (1838–88) and the French artist Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) came to prominence at this time with their realistic depictions of rural scenes, particularly shepherds with their flocks.

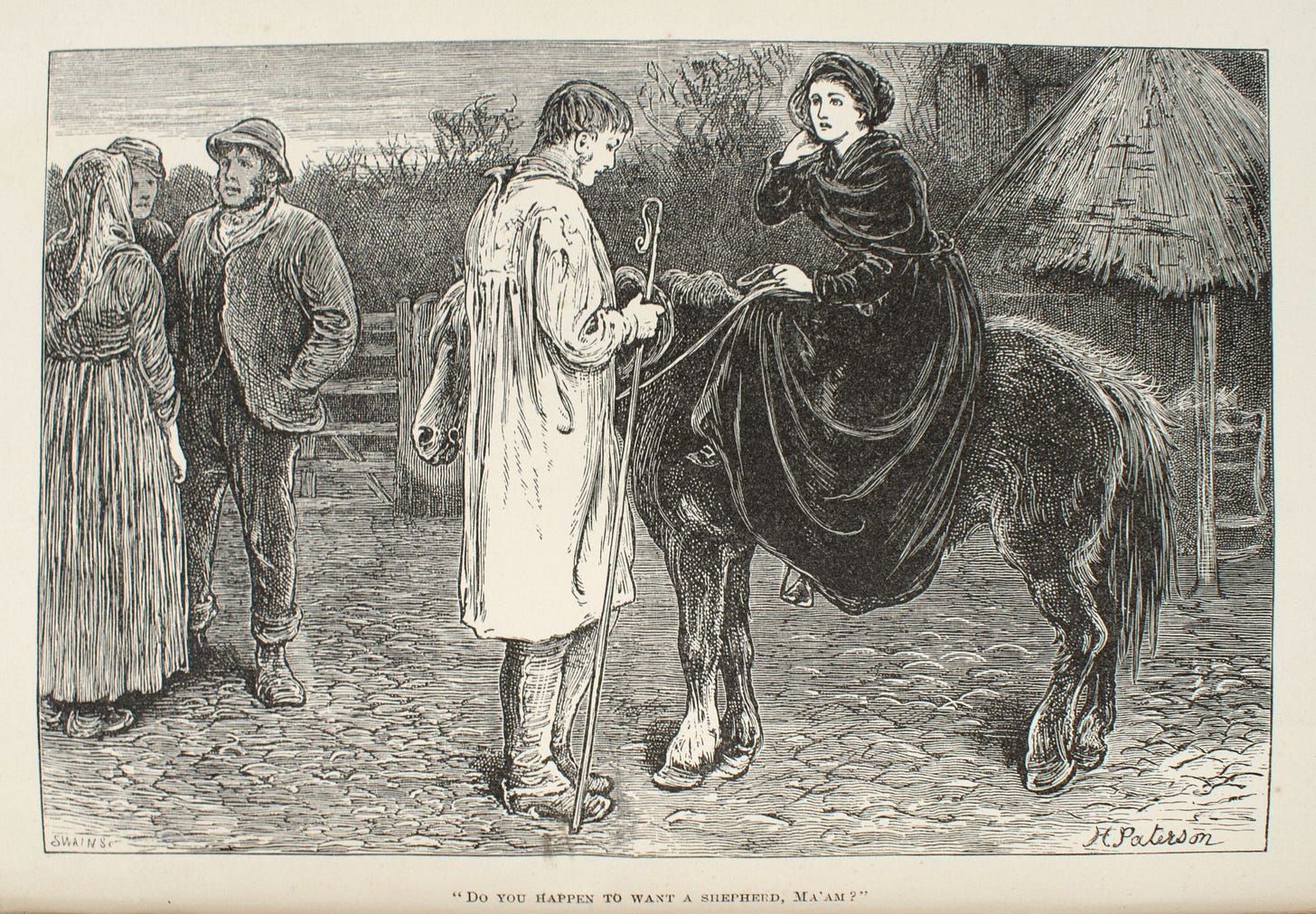

In 1874, Thomas Hardy's publication of Far from the Madding Crowd portraying the skilled, steady and honourable shepherd Gabriel Oak, who remained loyal to the capricious Bathsheba Everdene – and ultimately won her hand – found a wide audience. It established Hardy as a successful author of novels that evoked a closely observed rural setting. It seems that the shift towards urban life sparked a nostalgia for a disappearing pastoral existence, albeit one often of hardship and tragedy.

The population of Great Rollright declined during this period. Between 1841 and 1901, it dropped from 459 to 318. The social composition also changed. Whereas once the village’s predominant make up was of agricultural labourers and tenant farmers with absentee landowners, it now had resident gentry. In the 1890s, Alexander Hall moved into the manor. Page describes in his paper on ‘Social Character and Communal Life’ for VCH Oxfordshire how: ‘Following Hall’s arrival the cricket pitch moved to the manor house grounds, where other activities included an annual flower and vegetable show.’ It was in this more gentrified context that Richard Widdows emerged as an elderly village ‘character’, distinguished by his great age and occupation as a shepherd.

The photograph of Richard Widdows was posted on Rootschat in 2015 by the wife of a descendant of Widdows. I have attempted to contact her to seek permission to republish it. It could be by Percy Simms, the Chipping Norton-based photographer, who took a number of pictures of Widdows in 1909 for local papers, celebrating him as a centenarian. The writing at the bottom states ‘age 104’, like the captions to Simms’ other photos.

It's so interesting to read the social context of Widdows's status as a shepherd and interesting that he returned to that definition of himself, once retired. How fascinating to consider the artistic context too as well as the literary one. This definitely makes me want to read 'Far from the Madding Crowd' again, having not read it for about forty years!