When you enter St Andrew’s churchyard through the lychgate at Great Rollright, Richard Widdows’ gravestone is the first one you see. It stands apart, on slightly raised ground to your left. Large and prominently positioned, it’s in a dark red stone and generously inscribed.

This is not the headstone of a landowner or a prosperous farmer. It is, as the inscription says, of a humble man who died at the age of 104 in 1910 – a shepherd. It was erected by public subscription.

Ever since I first noticed Widdows’ headstone on a daily walk during the pandemic, I have not been able to stop wondering about the life of this shepherd who lived to such an astonishing age in the early 1900s. Curiosity has turned into determination (my husband says ‘obsession’): who was he, and what would life have been like for him in Rollright over a century ago?

Beginnings

Widdows’ origins are hazy. He did not start life in Great Rollright. He was born before the registration of births in 1837, so it is difficult to verify an exact year and date of birth for him. In the seven census returns that he entered between 1841 and 1901, his date of birth varies between 1808 and 1819 with only the same date provided in two successive censuses when it was listed as 1808. His place of birth is also inconsistently recorded as: Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, Brailes, Warwickshire and Burmington. (This is not quite as off the mark as it might seem as Great Rollright is on the Warwickshire border and only a few miles from Gloucestershire.) The spelling of Widdows’ surname also fluctuates between Widows, Widdows and Withers.

This fuzziness with the facts is difficult for us now to understand when data is everything. What it does strongly suggest is that Widdows was illiterate, which would have meant his census returns were submitted via an intermediary. In the middle of the 19th century, almost a third of men failed to meet the lowest bar of literacy – being able to write their own name. Between 1841-5, 32.5% of husbands signed the marriage register in England with a mark. With no national provision of education in the early 19th century and a working life that started in late childhood, Widdows would have had little, if any, opportunity to learn to read or write.

It is almost certain that Widdows started life in the small village of Burmington, near Shipton-upon-Stour in Warwickshire. In local newspaper reports in the final years of his life and in his last few census returns, he consistently gives this as his place of birth. The first official record that we have for Widdows is from 1835 when he married Eliza Penn in Stretton-on-Fosse, Warwickshire, where he was listed as resident – a village that is 4 miles from Burmington and 11 miles from Great Rollright.

Author David Watkins, who researched Widdows’ biography for the website Cecil Sharp’s People was unable to trace any record of baptism for Widdows at Burmington, but found a ‘Richard Widows’ baptised at nearby Brailes church in May 2011, a son of John and Elizabeth Widows. This supposition is supported by the marriage of a John Withers to an Elizabeth Smith in Burmington in 1809. His mother Elizabeth Smith must have come from Burmington, having been baptised there in 1789.

At the mercy of the parish

A local newspaper article from 11 October 1905, ‘A Great Rollright Centenarian: sketch of his career’, Oxfordshire Weekly News, publishes Widdows’ reminiscences on his ‘hundredth’ birthday, and provides his own account of his childhood.

Born in Burmington, his father was a ‘Great Rollright man and a soldier. Not being fond of his profession, he deserted as many as three times. When he was retaken (and this occasion Mr. Withers well recalls), he was in the “condemned regiment,” or in other words the “forlorn hope,” and was not heard of again by his son. Mrs Withers married again and went away to Exeter.’ In his account, Widdows also recalls the victory celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 at Burmington, when he must have been four or five, where ‘an effigy of Napoleon’ was ‘carried around the village on a donkey’.

Family life in Burmington, however, must have been brief as he was abandoned by both his parents. Widdows and a younger brother were left to ‘the mercy of the parishioners. They spent their infancy in the institution which in those days took the place of the present workhouse.’

Widdows does not recall where this institution was located. Burmington was too small a parish to have supported a workhouse: hardly more than a hamlet, its population hovered at over 100. Shipston-on-Stour, a couple of miles away, had a workhouse housing 30 people in 1776. After the Poor Law Act of 1834, a much bigger workhouse was built there, the Shipston on Stour Poor Law Union, that accommodated the poor from parishes across Warwickshire and Worcestershire.

The parish didn’t support abandoned children for long, though. By ‘the age of 10 or 11 Richard commenced to work for his living, and being big enough to drive the plough went to work at Coombe Farm’. This move to a farm in Great Rollright goes unexplained, but it seems likely that it was connected to his father’s roots in the village. In the 1820s, Coombe Farm was farmed by tenant farmer Thomas Harbidge and his family. A restless adolescent, however, Widdows didn’t remain in Great Rollright for long:

‘Soon after this he decided to seek his fortune further afield, and went with some other youths to Birmingham. But things did not turn out as they anticipated, and he returned to Great Rollright.’

Return to Rollright

It seems that Widdows returned to Rollright for work soon after his marriage to Eliza Penn in 1835. He must have been drawn back by local family connections. In such an isolated and poor parish as Great Rollright, most labourers were born locally. It was not the kind of place you came to seek work. Two and a half miles north of Chipping Norton, Rollright is set high off the ancient ridgeway and 220 metres above sea level. It is a bracing environment in which to labour outdoors all year round. With no resident gentry, absentee landlords, it was largely farmed by tenant farmers during the 19th century. Ownership of the land, farmhouses and cottages was primarily divided up between two manors – Great Rollright Manor and Brasenose College. In the village, there were 70 men and boys working for farmers as agricultural labourers.

Widdows’ return to Rollright could not have been at a worse time. It was in the middle of an acute agricultural depression. Reginald W Jeffery describes it in his history of the village, The Manors of Advowson of Great Rollright (1927): ‘landlords, farmers and labourers all suffered. In 1835 the depression of Great Rollright was so extreme that the landowners were obliged to assist their tenant-farmers by a return of 15% of the rents.’ According to the census returns of 1830, poverty had already previously driven 67 of Rollright’s inhabitants to migrate to the United States.

By the 1841 census, Widdows was living at ‘Fletchers’ Combs Farm’ in Great Rollright with his wife Eliza and four children under five. The farm was a remote field homestead, located a mile northwest of the village, adjacent to Coombe Farm where he had worked as a boy. Widdows’ occupation was listed as ‘agricultural labourer’. (It only appeared as ‘shepherd’ in the 1861 census.) His employer was William Fletcher, a young tenant farmer in his early 20s from Gloucestershire. In 1851, Fletcher had 9 labourers working for him on the 297 acres he rented off Brasenose College.

Family life

For about forty years, Widdows worked for the Fletchers living in a cottage with his family. Feeding and clothing growing children must have been a constant struggle. The lack of healthcare and medical provision for anyone but the wealthy also made life itself precarious. Without contraception, children could not be planned, and many women died in childbirth. We do not know Eliza’s cause of death, but in March 1849 Widdows’ wife passed away at the age of 34.

In the 1851 census, Richard Widdows is listed as a widow living alone with his five children: Ann 15, John 13, Elizabeth 11, Mary Ann 8 and Joseph 4. Three years’ later in 1854, Widdows married for the second time, Jane Wiggins, a spinster from Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire.

By 1861, Widdows had three daughters with Jane. None of Widdows’ children from his first marriage with Eliza were now living with them: Widdows’ eldest daughter Ann had married stonemason Thomas Bull in 1854; Mary Ann also seems to have married in the Chipping Norton area in 1857: and John, whose occupation was given as ‘farmer’s boy’ in 1851, remained in Great Rollright. He appears in the 1871 census as an ‘agricultural labourer’ living with his wife and two young sons in a cottage belonging to farmer Richard Berry. Widdows’ youngest son Joseph died in 1861 at the tender age of 14.

With Jane, Widdows had six children, making him a father of eleven in total. The two sons he had by this second marriage – Solomon and David – both followed their father on to the land as agricultural labourers. Sarah, who was the youngest child, born in 1871, was referred to as ‘imbecile’ in the 1891 census. A year later in 1892, she died at the age of twenty-one.

It is a testament to Widdows’ remarkable longevity that he went on to outlive not only his second wife, but also seven of his eleven children. Jane died in 1902 at the age of 83. When Widdows was featured as a centenarian in the 16 October 1909 issue of The Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, it recorded: ‘He has three daughters living and numerous grandchildren and great grandchildren.’

A long life

On Widdows’ headstone is inscribed a verse from the Bible that evokes a lengthy and wholesome life on the land: ‘Thou shall come to thy grave in a full age like as a shock of cometh in his season’ (Job v 25).

The efforts that the local community made to mark Widdows’ life, raising money for a significant memorial by public subscription, suggests what great veneration he was held in. In October 1907, local landowner Richard Berry wrote to King Edward VII’s private secretary on his behalf and received a letter back from Balmoral congratulating Widdows on his ‘102nd’ birthday. On his retirement in the mid 1870s, Widdows, his wife and three of their children moved from the Coombs, a valley on the outskirts of the village, into a cottage at its very centre near the church, where he was a regular church goer.

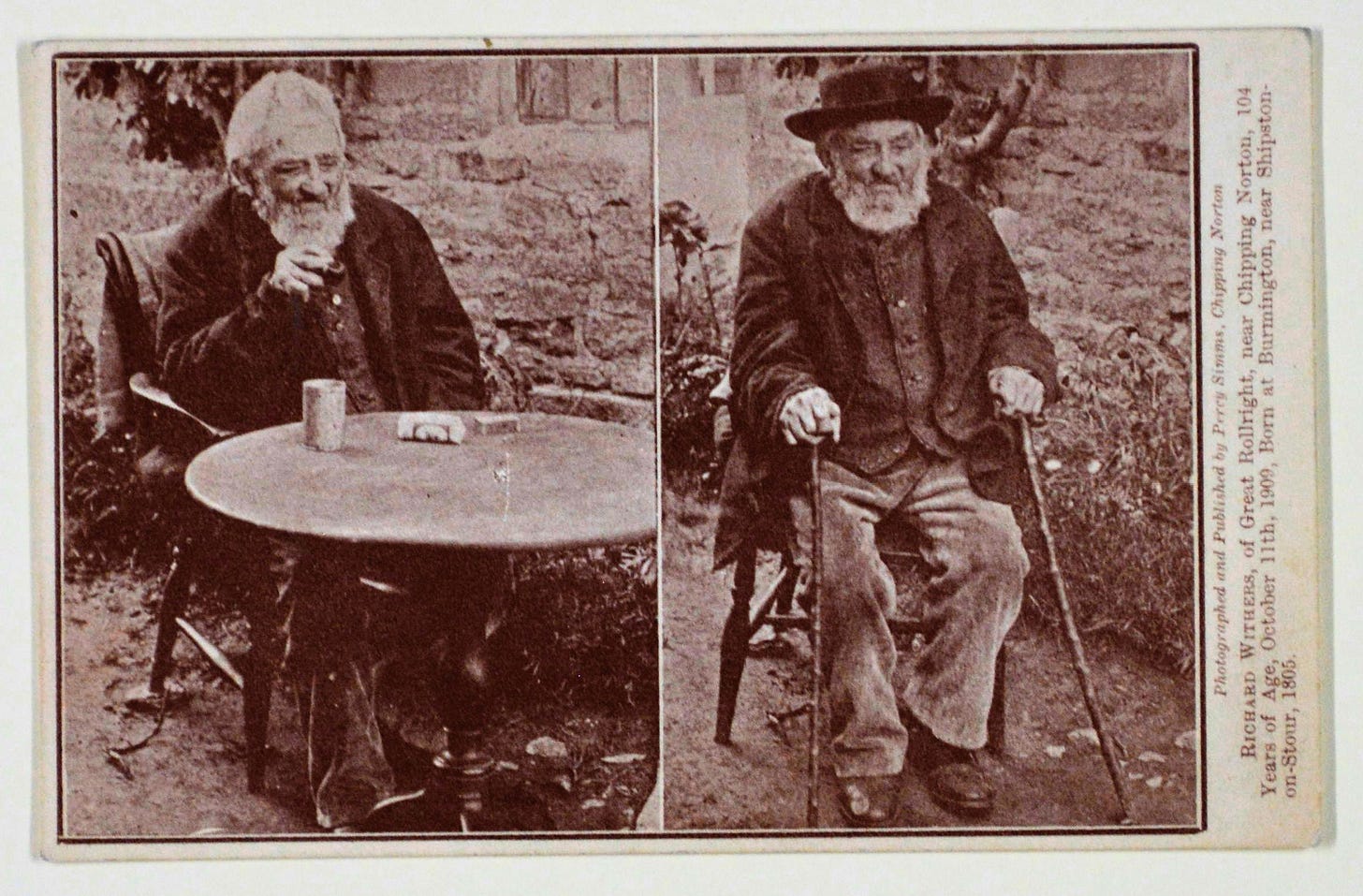

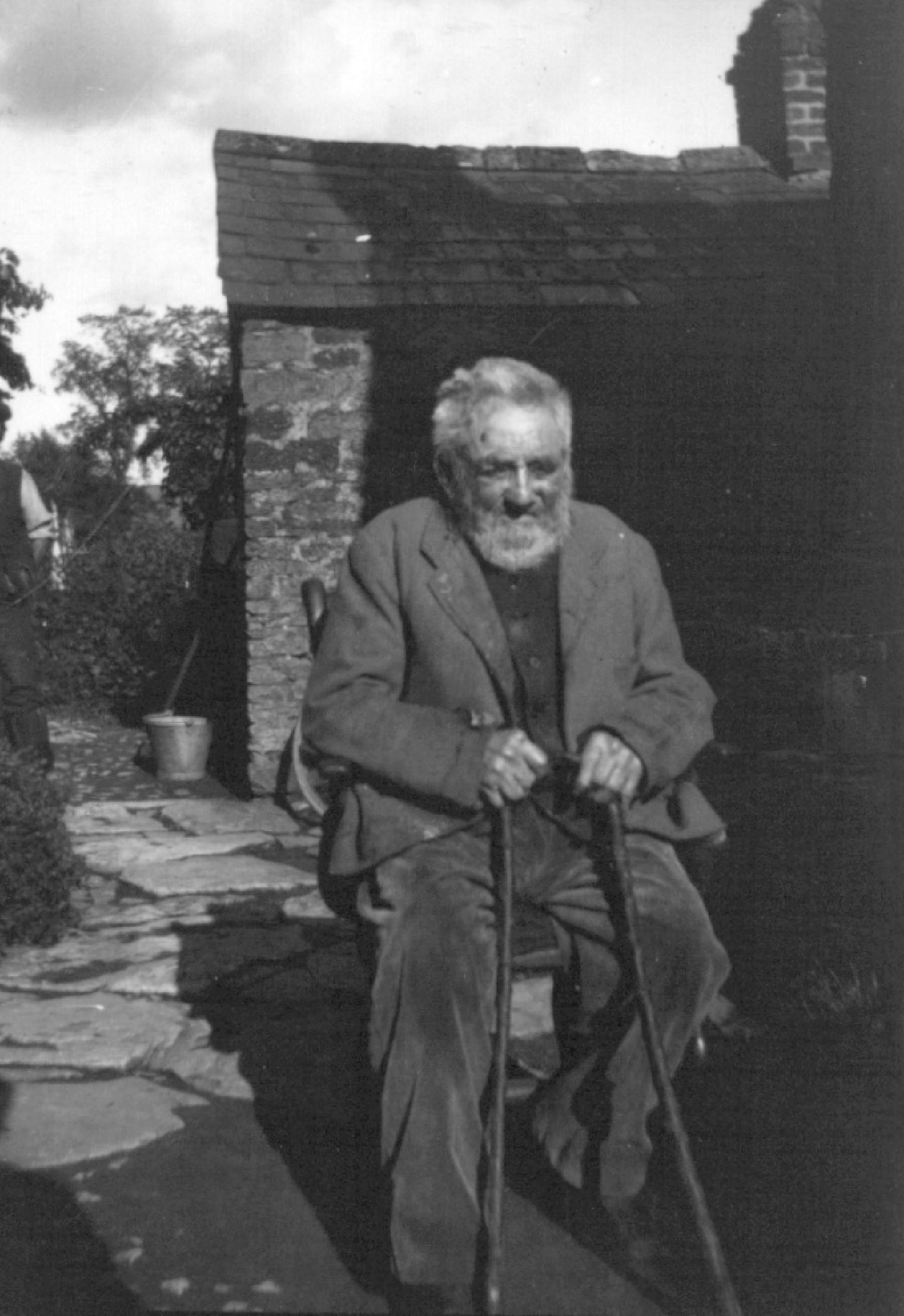

By Widdows’ ‘104th’ birthday in October 1909, his great age was being covered on the inside pages of press across the country. The Oxford Journal Illustrated and The Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic featured photos of him by Chipping Norton-based photographer Percy Simms. Earlier that summer, in July 1909, the folk song collector Cecil Sharp visited Widdows, as part of his travels in Oxfordshire, and took down a song from him ‘Young Man from the Country’: an early music hall hit that was featured in mid 19th-century broadsides. With a refrain ‘I’m a young man from the country and you can’t get over me’, the song is written from the point of view of a country lad who proves too bright to fall for the low tricks of towns people. Though Sharp did not obtain it from anyone else at the time, Alan Lomax recorded a version from a local singer in Suffolk in 1953.

The historian Jeffery gives us a glimpse of Widdows and his character, writing 17 years after his death in a footnote to his book: ‘When this old man was 103 he quavered two old folk songs to Mr C. Sharp. The same year he told Mr. Montague Randall that he still managed to get to church but that he had given up gardening when he reached the age of 100. He was an inveterate and very heavy smoker to the day of his death.’

Given the hardship of Widdows’ childhood and later life, the uncomfortable domestic conditions he endured, living in cramped, damp, cold and dark stone cottages, without running water and electricity, and the ongoing challenge of feeding himself and his family, his great age was extraordinary. It is no surprise that this village character captured the imagination of the press and local community.

When you do the maths, Widdows could not have been as old as the 104 marked on his grave. Taking the baptism date of May 1811, Widdows would have just missed being a centenarian, and been 99. (In old age he celebrated his birthday on 11 October, giving us a birth date of October 1810.) This may not have the dramatic impact of 104, but remains an exceptional age for the time – almost double the median. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) gives the average life expectancy for males in 1910 as 51.

With thanks to local history researcher and author Carol Dingle who generously shared her knowledge with me and provided significant guidance. Also, to Warwickshire County Record Office and the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at the English Folk Dance and Song Society for supplying photographs of Widdows.

This article was originally posted on 28 December 2023; it was significantly revised on 14 January 2024 to include new information about Richard Widdows’ childhood.

Thank you for inspiring the project on our weekend away in Bakewell! Your words of encouragement mean a lot to me ❤️

Such a fascinating read, Helen! Your research is impressive and your interest in Widdows really draws us in and intrigues us about what else his life will reveal about the history of Great Rollright. What an incredibly strong man to endure so much and outlive so many! Wonderful writing indeed...