Why shepherds can live to a great age

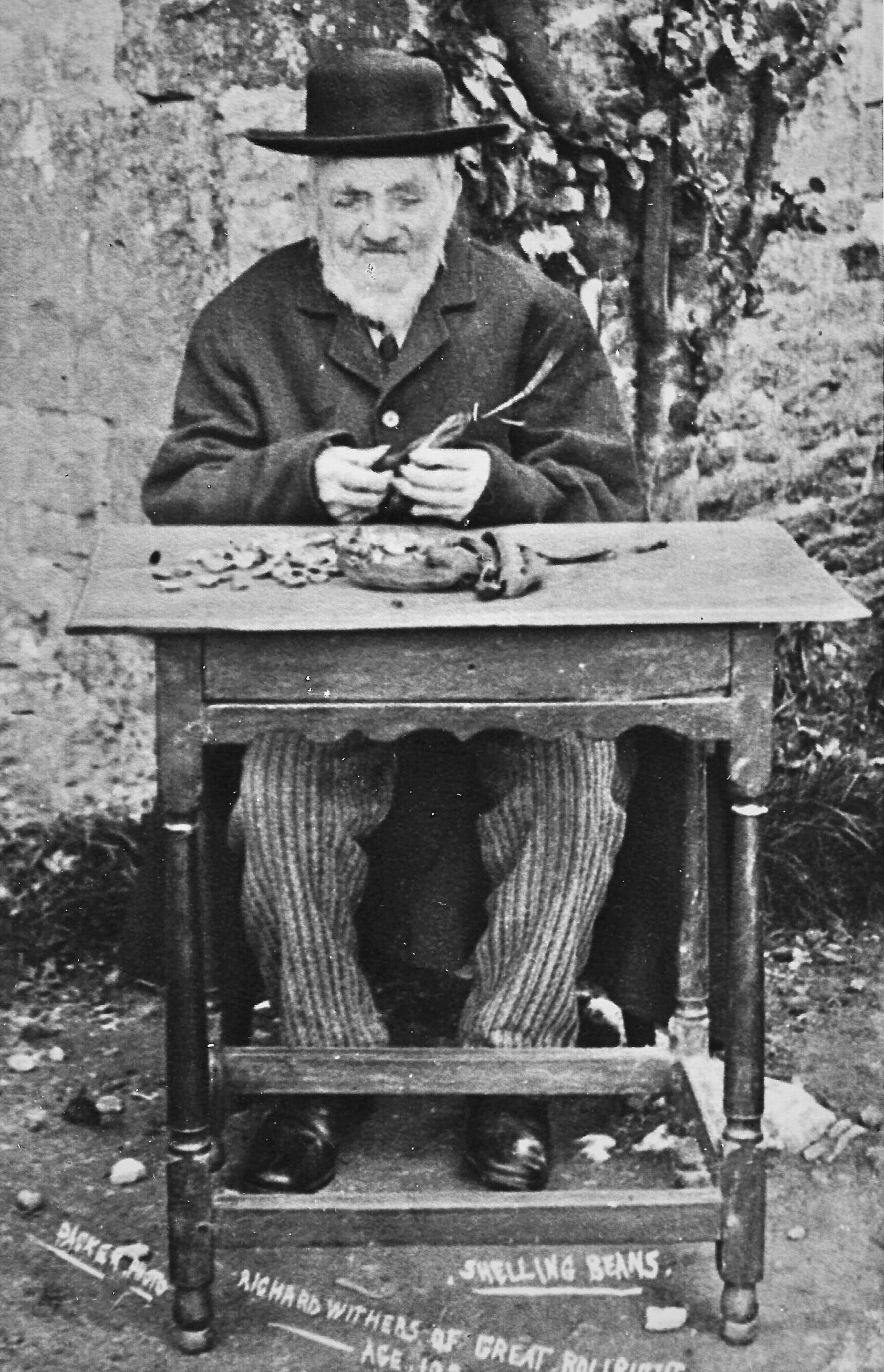

Could a shepherding lifestyle be the secret to Richard Widdows’ longevity?

Living to be a centenarian, or even close to a hundred, was extraordinary in 1910 when Richard Widdows died. However, it was even more exceptional if you were a man: the average life expectancy was 51 for men and 55 for women. Regardless of time, geography or culture, women usually live longer than men. According to the Office for National Statistics, in 2020 there were twice as many women aged 90 years and over than men in the UK.

It is unlikely that genetics can account for Widdows’ great age, as only 3 of his 11 children seem to have survived him. So, what were the lifestyle factors that could have influenced his longevity?

What Richard Widdows and Sardinian shepherds have in common

There are few populations in the world where men live as long as women. One exception is a cluster of villages in the mountainous regions of Sardinia. These came to international attention when medical researcher Gianni Pes shared his findings at a conference in 1999. Pes and his collaborator Michel Poulin ‘drew concentric blue circles on the map highlighting these villages of extreme longevity and began to refer to this area inside the circle as the blue zone’. The concept of ‘blue zones’ – areas of the world in which people live exceptionally long lives – have since been popularised in books and a TV series by journalist and broadcaster Dan Buettner. (For coverage of Sardinia, see episode 2 of the Netflix series ‘Live to 100: Secrets of the Blue Zones’, 2023.)

Pes and Poulin discovered that longevity among men was particular to the mountainous areas of Sardinia where the male population were shepherds and lived traditional lifestyles in communities that remained isolated until the first half of the 20th century. The type of ‘low intensity physical exercise throughout life’, which shepherds were exposed to, increased their 'cardiorespiratory fitness’. ‘Farmer’s work was concentrated in time and was usually very wearing, whereas that of shepherds was more moderate, constant every day through the year, and implied walking a long distance on steep paths.’

Although Great Rollright is not 700 metres above sea level like the blue zone villages of Sardinia, it is at an extraordinarily elevated position. Most of the village is located at above 200 metres on a ridge of high ground, surrounded by semi-enclosed valleys. Anyone who has tried to ride a bike in Great Rollright will know that there is no way in or out of the village that does not involve a steep hill. The cottage at Fletcher’s Coombs that Richard Widdows lived in until his late 60s or early 70s was over a mile outside the village in a valley. To reach a flock of sheep, arable fields or the village required a lot of uphill and downhill walking.

A traditional lifestyle

Widdows would not only have had this type of physical activity in common with shepherds in Sardinia, but also a diet full of fresh vegetables. Widdows grew his own vegetables until he was elderly. In June 1905, in a column in the Oxfordshire Weekly News, when he was supposed to be almost 100, he was reported as having given ‘a basketful of potatoes’ to the guardian of the parish that ‘he had planted himself, attended to, and dug up’.

In Pes and Poulin’s paper on men living as long as women, they also highlight that in the villages of Sardinia: ‘oldest men are the target of intense attention within the family but also in the local community, which may bring them support for living longer’.

Widdows had two wives: Eliza (nee Penn), who he married in 1835, but died in her mid 30s in 1849, after giving him 5 children; and Jane (nee Wiggins), who he married in 1854 and he had a further 6 children with. Jane was about 12 years younger than Widdows and lived to a good age, dying at 83 in 1902. After Jane’s death, Widdows continued to benefit from the devotion and care of his neighbours. Montague Rendell, the rector’s son, who published his reminiscences of village life in the Bells of Great Rollright (1947), recalled Widdows being attended to by his next-door neighbour Ann, ‘a devout and scripture fed woman’, and being visited regularly by the rector and his family.

In his dotage, Widdows gained local veneration and celebrity. His ‘102nd’, ‘103rd’ and ‘104th’ birthdays were village celebrations, marked by the ringing of church bells and the lady of the manor baking a cake with visits from his daughters and grandchildren. Landowner Richard Berry wrote to the King’s Private Secretary and received congratulations from Balmoral. Between 1893 and 1910, Richard Widdows (referred to as Withers) was the subject of 14 columns in the Oxfordshire Weekly News. These marked his birthdays, but also included his reminiscences and updates on his health, and eventually an extensive obituary and notice of the public subscription for his gravestone. The congratulatory message from Edward VII on his ‘102nd’ birthday in 1907 sparked national coverage of Widdows’ great age from the Daily Telegraph & Courier and local papers across the country and Ireland, even making it across the Atlantic to the inside pages of the Ottawa Free Press.

A sense of belonging, purpose and being part of a faith community have also been identified as some of the most important 9 lifestyle habits in blue zones that contribute to a long life. Rendell describes ‘Old Withers: A faith like his was the very life and being of an upright “working man” of that epoch. . . Great Rollright village embodied a community ... strong in faith and principle and also in the best kind of family pride.’

A blue micro dot, if not a blue zone

Writing in 1927, in From the Manors and Advowson of Great Rollright, historian Reginald W Jeffery extolled the ‘excellent’ health of the population of Rollright. He noted that ‘from 1908 to 1910, the ages of those buried were 75, 82, 70, 83, 104 [Widdows], 76, 70, 73, 78, 1 and 49’. There is no doubt that lifestyle habits contributed to Widdows’ extraordinary longevity and the better than average life expectancy of villagers at that time. Widdows was also fortuitous. An inveterate smoker, he was purported to have consumed 4oz of tobacco a week!

With thanks to Carol Dingle for providing the quote from Montague Rendell and to Chipping Norton Museum and Oxfordshire History Centre for supplying the photos.

There we are. Lots of gentle walking... I reckon there would have been cheese too. I bet that helped. Who could not live a long time when exposed to cheese.

I loved it when you told us that he'd actually featured in all those newspaper columns. It must be very exciting to start a research project then to find so much more material is available than you at first imagined. It's so fascinating that walking these inclines has such a benefit to us - and for Widdows, even with all that tobacco!