The slippery nature of spelling in previous centuries is unfathomable to us today. Whereas once place names and surnames altered and morphed, often several times within a lifetime – as in the case of shepherd Richard Widdows (see below) – our expectation is that they are universally fixed and standardised, appearing consistently in official documents and data.

Over the last thousand years or so the spelling of ‘Rollright’ has gone through numerous modifications. Between 1086 and 1670, there were 99 variations of the name. It was only in 1791 that it appeared in its present form. In his history of the village, The Manors and Advowson of Great Rollright (1927), Reginald Jeffery went to the trouble of collating all the variants in an appendix

In the Domesday Book , Great Rollright first appears as ‘Rollendri’. With 37 households recorded in the village, surprisingly it was in the top 20% of settlements in terms of size in the country. The population of the village is estimated to have been about 160 – with approximately 4 people in each household. This gives a sense of how very thinly and lowly populated England was with a total population of about 1.2–1.5 million with only 18 towns over 2,000 inhabitants.

Situated high on the ancient ridgeway, Rollright has used the prefix ‘Great’ for over a thousand years to differentiate it from the small village of Little Rollright located in a valley near the Rollright Stones.

The meaning of the name ‘Rollright’ is long associated with the megalithic Stones, which have been a significant landmark and source of local curiosity for centuries. Located a couple of miles west of Great Rollright, they are almost an hour’s walk from the village. The King’s Men, the ceremonial stone circle, is over four thousand years old, dating back to the late Neolithic age, c 2,500 BC.

In a separate appendix, Jeffery provides seven definitions of the meaning of the name ‘Rollright’ from authorities dating back to the 17th century. The first of these, Camden, writing in 1636, erroneously connects the origins of the Stones and the place name to the Viking leader Rollo. Many of the subsequent proposed derivations are also associated with theories attached to the history of the Stones. Deftly Jeffery does not come down on the side of any single theory.

Historian Mark Page provides the most current thinking on the meaning of the name in his paper, ‘Landscape, Settlement and Buildings: Great Rollright’ , for the Victoria County History Society: ‘The place name may derive from Old English “Hrolla’s landriht”, meaning the “privileges belonging to Hrolla as landowner”; a more likely alternative, however, is a Brittonic phrase “rodland rïcc”, meaning the “narrow gorge by the wheel enclosure”, a reference presumably to Danes Bottom and the King’s Men stone circle.’

Widdows, Widows or Withers?

It is perhaps even more tricky to get our heads around the variations in shepherd Richard Widdows’ surname, which fluctuated throughout his lifetime. This was presumably not just spelling, but also the way that it was said – shifting between ‘Widdows’ and ‘Withers’.

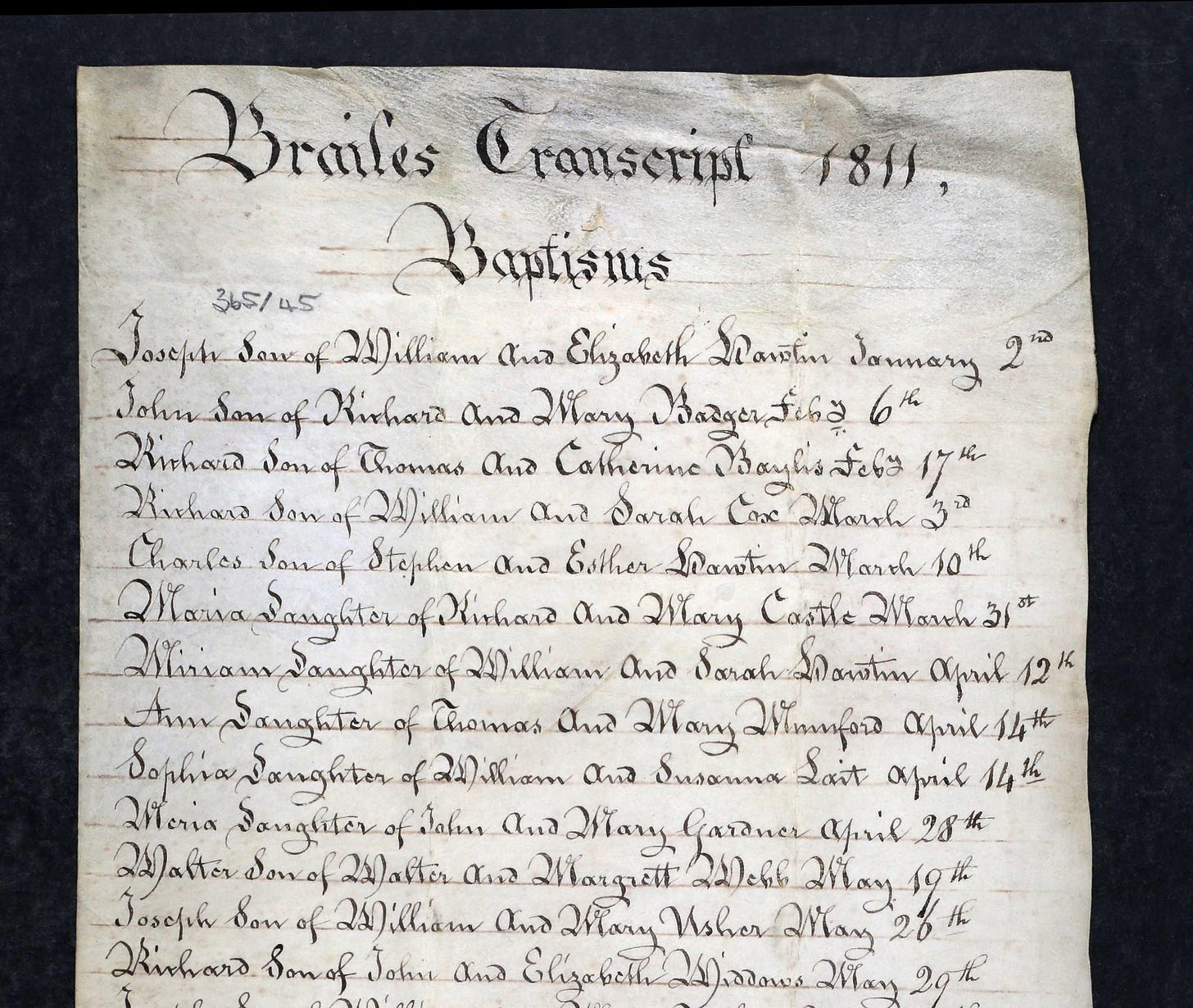

In the records for his baptism (above) and first marriage (below), his name is listed as ‘Widdows’. In the 1841 census, when he was living in Great Rollright with his wife Eliza and three young children, the family’s name is given as ‘Widows’ with only one ‘d’. In all the subsequent census records from 1851 to 1901, Widdows’ name is consistently given as ‘Withers’. In the register of his second marriage to Jane Wiggins, his name is also written as ‘Withers’. His children continued to use the name Withers.

So why did the shepherd’s name appear as ‘Widdows’ on his gravestone? Writing seventeen years after his death, Jeffery gives us a clue in a footnote about the inconsistent spelling of names: ‘In 1910, when Richard Widdowes died, at the age of 104, there was difficulty as to his name. He had always been known as Withers, but the baptismal register of his native place showed Widdowes and this was engraved on his tomb.’ There are a couple of ironies about this entry: firstly, Jeffery incorrectly spells his name with an additional ‘e’ that does not appear on his baptism certificate or gravestone (perhaps his own joke); secondly, in sourcing Widdows’ baptism register Richard Berry, who organised the public subscription for Widdows’ tombstone, must have also realised that Widdows, baptised in 1811, was unlikely to have been 104 – the age recorded on his headstone in 1910.

When I researched Richard Widdows’ life for my first post, I made the assumption that he was illiterate. This was only confirmed when I found the registration of his first marriage to Eliza Penn in 1835, in which he is recorded as having signed with ‘his mark’ (above). To have been unable to read and write in the 1830s was very different to being illiterate in 1910 when he died. The Victorian era was one of increased record keeping, bureaucracy, education reform and written communication with the boom of newspaper, magazine and book publishing. By the end of his life, Widdows’ inability to read must have hindered him in the accessing of information, just like someone in their nineties now without a smart phone or online access finds themselves placed at a disadvantage. Widdows was perhaps one of the last of a generation in which knowledge was kept alive in rural communities through verbal storytelling and folk songs and the way that a name was written and spelled was of little or no consequence.

Helen,

I note with interest that the “end & and” in the spelling of Rollright had disappeared by 1600. I also note the “roll” was spelt in different ways which is surely a reflection of how the word was spoken in the local accent of the time – Rowl, Roul, Rol, Wroul, Rowle, Roule, Roll, Rolle. All these spellings are clearly expressions of virtually the same spoken sound. I am not familiar with the old fashioned spoken accent used in this part of the country but one thing is certain is that the animal, which we, who use Received Pronunciation, RP, call a sheep was spoken of here to sound like “ship”; hence the present names of a number of towns and villages – Shipton.

Next thought: it was the great Doctor Johnson who was almost the first to try to bring order to the English language with his dictionary from which the spelling of words inevitably followed.

You will have realised by now that what I am saying is that Widows, Widows, Widdowes, Withers are all the same sound.

I suggest that you look at “Grimm’s Law” in Wikipedia which clearly shows how consonants are related and how the sounds change and relate to one another.