Today, Christmas is undisputedly the biggest annual celebration in the British calendar. This was not always so. Most of the hallmarks of a contemporary Christmas – the Christmas tree, baubles, crackers and the Christmas card – were Victorian inventions, even its essential character as a holiday of get-togethers and family gatherings.

So, how was Christmas experienced in the late 19th century in Great Rollright? The scope for merriment and spending time with nearest and dearest was wholly dependent on material resource. There was a significant disparity in the way that farmworkers, like shepherd Richard Widdows, and middle-class inhabitants, such as farmers and the Rector Rendall and his family, observed the day.

A shepherd’s Christmas

Christmas celebrations were by necessity modest for agricultural labourers and their families. Wages remained low until the end of the century. At the end of each week, there was little left over for anything but the most essential food supplies. For those who lived beyond working age, their existence was even more precarious. Living to nigh on a hundred in 1910 meant for Widdows several decades of being supported by the parish. He was wholly dependent on handouts from the church and the village’s charities. His home, a cottage adjoining the churchyard was provided by guardian of the poor and churchwarden, yeoman farmer Richard Berry. It was only in the final couple years of the shepherd’s life that provision was made for a means-tested state pension of 5 shillings a week. In 1908, the Old Age Pensions Act was passed through Parliament by Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Loyd George.

Until 1871, when Boxing Day was introduced as a public holiday in England, farmworkers only had Christmas Day off work. This did not, though, exempt those with responsibilities for livestock from their duties. As a shepherd for farmer William Fletcher for over thirty years (1841 – late 1870s), Widdows would be expected to check on the flock. Over the holiday period, poaching was rife. The local newspapers reported regular occurrences of stealing game and sheep and cow rustling in Rollright and neighbouring villagers.

Villagers who were churchgoers or chapelgoers attended a morning service. Widdows was a regular member of the congregation at St Andrew’s. Young children might receive modest treats from their parents on Christmas morning – an orange, nuts or a ribbon – unless they had a sister in service who sent a package home. Cottages were decorated with foliage scavenged locally – holly or evergreens. The highlight was the Christmas dinner, typically a joint of beef, gifted by a local farmer. In the Oxfordshire Weekly News in December 1879, the Rector Rendall and Richard Berry are reported distributing joints to all Berry’s employees and the aged poor of the parish. It is most likely that Widdows was a recipient. The roast would have been followed by a ‘plum pudding’ – a suet duff sprinkled with raisins. This might be accompanied by beer or a homemade wine.

Christmas did not provide farm labourers with the opportunity for family reunions as daughters who were domestic servants could not be spared by their employers during the festive season. Five of Widdows’ seven daughters left home in their early teens to take up positions as far as way as Clerkenwell in London and Wales. (The eldest daughter was exempt from service as she married early and the youngest daughter who died at 21 was classed as an ‘imbecile’ on the census.) Widdows’ eldest son emigrated to New Zealand and his three younger sons, who lived and worked locally, did not survive beyond their early thirties. There was little opportunity for wider socialising as there was not a sufficient surplus of food and drink to share with friends and neighbours. It was a day for staying at home and battening down the hatches in front of the fire. In Lark Rise, Flora Thompson characterises Christmas day in an Oxfordshire village in the 1880s as ‘quiet’, a ‘super Sunday’.

The Rendalls

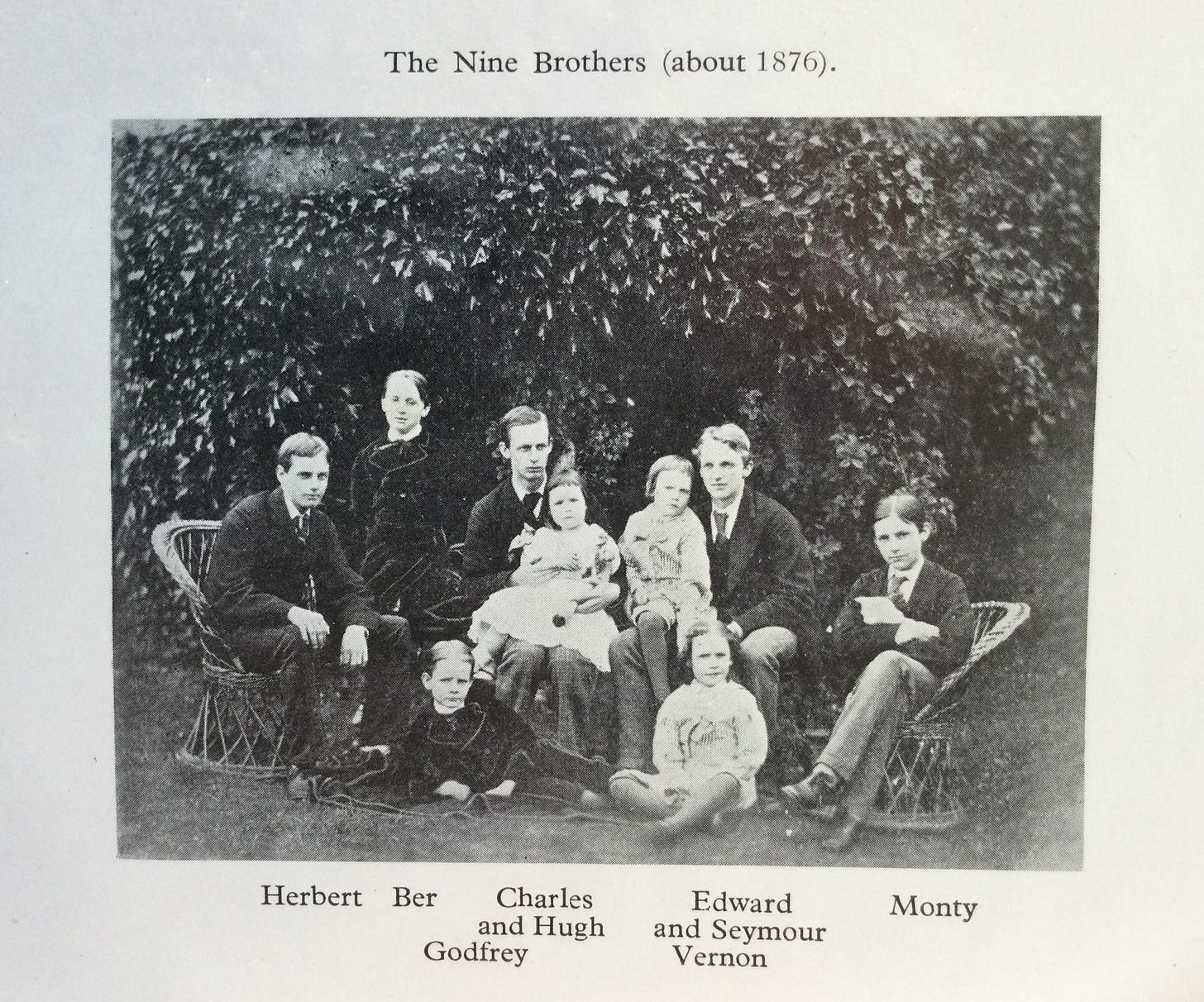

In 1855, Henry Rendall (1817–1897) arrived in Great Rollright with his new bride Ellen Harriet (1830–1905), succeeding the prodigal Joseph Heathcote Brooks as rector. In 1851, Brooks had fled abroad having shamed himself getting into irretrievable debt enlarging and aggrandising the rectory. Dismayed initially by the financial burden of maintaining such a large house on a living of £750 a year, the Rector and Mrs Rendall proceeded to fill it with children. Over the next 16 years, they had nine sons. Their only daughter, Mabel Jessie, died at 17 months.

The Rendalls maintained a minimum of four live-in servants during the rector’s incumbency. In 1871, this included: a 36-year-old nanny, Jane Gilkes, from neighbouring Wiggington; a 14-year-old under-nurse, Elizabeth Widdows, from Great Wolford in Warwickshire; a 25-year-old cook Emma Clarke from Appleton, Berkshire; and 25-year-old housemaid Jane Lewis from Salford, Oxfordshire. The household was also supported by a gardener and a maintenance man who lived out in the village.

The Rendalls epitomised the Victorian values of charity and administrative efficiency. As RW Jeffery describes in his history of the village: ‘After Mr Rendall’s arrival everything was much better managed. The keeping of accounts and the Churchwardens’ book alone show what a business-like man had been sent, at last, to conduct the spiritual welfare of Great Rollright.’ Remaining in Rollright for thirty-eight years, the Rendalls had a lasting impact on the life of the village. One of the most notable features of the church today is the lychgate erected in 1908 in memory of Ellen Rendall by her nine sons with their initials carved into the roof timbers.

Christmas with the Rendalls

The Rendalls’ celebration of Christmas exemplified the aspirations of the wealthy Victorian middle classes. A detailed account of the exuberances of Christmas Day, in c 1878, is provided in The Bells of Great Rollright, a collection of reminiscences, written in rhyming verse, by the rector’s fourth son Montague Rendall in his 86th year.

Christmas day started over breakfast with the opening of Christmas cards, a relatively recent innovation with the establishment of the Uniform Penny Post. The first Christmas card was sent by Henry Cole in 1843, the founding director of the V&A. The family attended Matins and Evensong with their father.

During the day, the children were sent outside for some bracing physical exercise to work up appetites for the Christmas fare ahead. The midday meal was cold as ‘retainers feasted on their Christmas lunch’.

Dinner was a formal affair requiring evening dress. The older boys, who attended Harrow, wore their tail coats. A grandmother and uncles and aunts were all present. This type of extended family gathering, uniting relations from across the country, was greatly assisted by the introduction of the railways. (A station opened in Chipping Norton in 1855.) The table was set with the finest dinner ware: branching silver candlesticks, salvers, fish slices, crested plates and Mrs Rendall’s best pink china. Two turkeys – roast and boiled – were served followed by a plum pudding, brought to the table by ‘smiling Polly, with blue flames licking round the berried holly’. The meal was completed by Elvas plums, almonds and Brasenose College port, accompanied by toasts to departed family members and friends in distant parts of the world. In subsequent years, fish and soup were added to the menu.

After dinner, the youngest Rendalls were brought downstairs by nanny from the nursery to join the family and crackers were brought out. Invented in the 1840s by Tom Smith, an enterprising East End baker, Christmas crackers were only introduced with an explosive pop in the 1860s. Still a novelty in Montague’s childhood, he describes their cracks waking up the farmyard, causing the ducks to quack!

The day came to a grand finale with the family and staff gathered around the Christmas tree, ‘a Giant for the Festival’, in the great open hall. The German fashion for Christmas trees was prompted in the mid-19th century by the royal family, informed by Prince Albert’s Saxon background. Richly ornamented with silver baubles, robins, stars and spangles, the Rendalls’ tree was candle lit. A fire was averted on this occasion by the quick-witted nanny, who prompted the maids to get the bellows. The administration of gifts was overseen by ‘the Queen of Givers’ Mrs Rendall, first to ‘all men and women on the rectory staff’, before the boys, according to age, were given paint boxes, novels, Christmas coats, footballs, chess sets, badminton racquets, boats and gollywogs.

Community spirit

In the 19th century, rural poverty excluded farmworkers from enjoying the Victorian Christmas innovations that the Rendalls embraced. The social classes were more polarised than they are today with agricultural labourers’ daughters leaving home as young teenagers to serve in middle- and upper-class households. Living and working in a village community, though, also meant that the better off members of society took responsibility for the welfare of the poorer ones. Not only did the farmers ensure that every household was provided with a joint of beef at Christmas, but the Rendalls also gave some 50 children of the parish clothes: boys received a new shirt and girls a petticoat (Oxfordshire Weekly News, January 1874). A tea party with cake and games was also organised for them on New Year’s Day. Year round, the Rendalls made regular visits to the poor and the aged. They were frequent visitors to Widdows in his dotage. Reflecting back some seventy years later on his childhood in Rollright, Montague remembers Widdows fondly as a Dickensian-like character who, with his unstinting faith and focus on the natural world around him, ‘was the very life and being of an upright “working man” of that epoch’.

Bibliographic sources: David Green (editor), An Oxfordshire Christmas (History Press, Stroud), 2009; RW Jeffery, The Manors and Advowson of Great Rollright (Oxfordshire Record Society), 1927; MJ Rendall, The Bells of Great Rollright: with chimes from Winchester and Butley (Warren and Butler, printed for private circulation only), 1947.

With thanks to Clara Freeman for the loan of her file detailing the history of the Old Rectory, researched by Carol Dingle.

So interesting and expertly constructed, Helen. Thank you for taking us back in time.

Thanks Brenda for all your support. Have a lovely Christmas! 🎄