Today, we know what shepherd Richard Widdows looked like because of the photography of Frank Packer and Percy Simms. The few photos taken of the centenarian capture his physical presence – his white beard, bright eyes and slight, fragile physique – while also conveying his sprite-like vivacity and inner strength.

The two photographers, who had competing studios in Chipping Norton, were active in the town and its surrounding villages from the early 1900s. Only one of them, Frank Packer, emerged as the chief photographer. This was due as much to his family’s entrepreneurial spirit and relentless drive as his photographic talents. During the Second World War, Simms closed down his business and Packer bought out his stock.

Like other photographers at the time, Packer took formal portraits of customers who visited his studio. He supplemented this business by photographing views of villages and landscapes across Northwest Oxfordshire and club days, funerals and fetes, which were all turned into postcards. Before portable cameras were affordable and available for personal use, the sale of postcards for a few pence provided the opportunity for people to purchase mementos of significant events and places. The local newspapers also commissioned him to take photos of weddings and individuals. Of the 52,000 surviving photographic images, taken by Frank and his son Basil between the early 1900s and the 1970s, about half were shot as postcards and half for newspapers.

It’s the Packers’ postcard business that is so precious to us today. It took Frank out and about to local events, but also prompted him to capture numerous views of outlying villages and buildings, including Great Rollright. The range of subjects that he took provide a unique insight into the social history of the area and how things have changed.

Getting started

Frank was brought up in Chipping Norton, where his father had a shoe and boot shop on West Street. His enthusiasm for photography was ignited in his youth by the interest of a neighbouring grocer. In their spare time, they got together to share their passion. Frank took photographs of people and views, which he hung outside his father’s shop, allowing him to build up his reputation and business gradually. When his father packed up the boot shop in 1900, Frank took over the premises. Soon afterwards, in 1903, he married 19-year-old Mary Todd, a grocer’s daughter from Alcester in Warwickshire. Mary was an enormous asset, running the business side of the venture.

Photography was more than a day job for Frank, he photographed every aspect of his life. When the Packers’ two children Basil (1907) and Gwen (1910) were born, he documented their lives from the very beginning. For others this could prove tiresome, as his daughter Gwen remembers: ‘Mum got fed up’.

In 1911, a shop came up for sale on the High Street in Chipping Norton. This was too valuable an opportunity for the business to miss. Frank’s great grandfather walked all the way from Fairford in Gloucestershire to buy the property for him. It provided a centrally located shop window where passers-by saw their photographs and were enticed inside. The shop at 28 High Street accommodated the family home, studio and dark room for the next sixty years.

The Studio

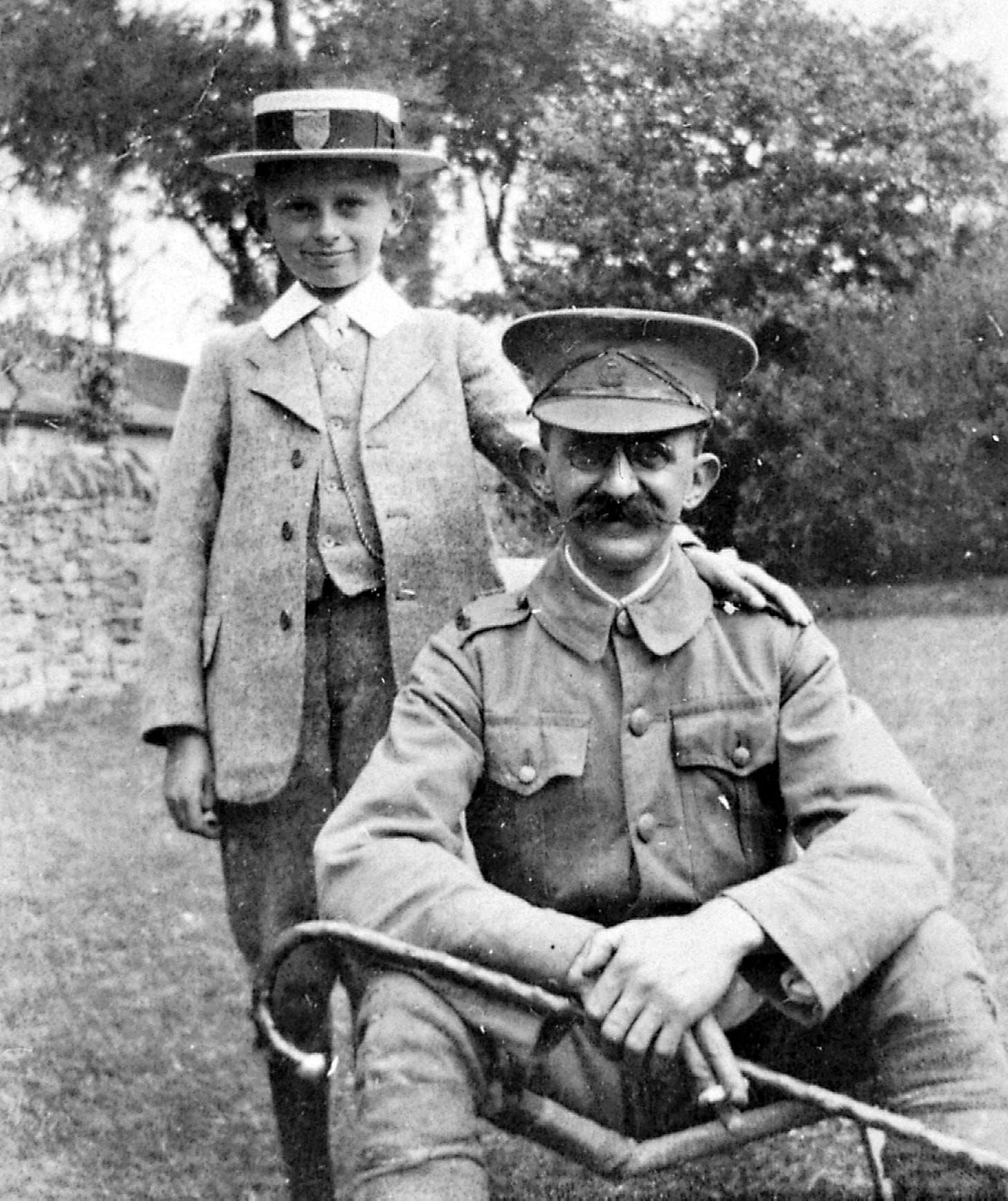

Before the war, Packer’s studio owned three plate cameras with wooden frames and brass fittings. Customers came into the shop from a wide area to have their photographs taken with a huge plate camera on a tripod. Frank took their photos with his head bowed, covered in a cloth. (See top photo.)

The other cameras were taken out to photograph local occasions and views. Before Frank acquired a motorbike, this heavy equipment had to be transported on a push bike (see photos below).

In an audio interview, Basil recounts being sent out to take photos of weddings. He was given three double dark slides with six plates in it and was told to take three different shots: bride and groom, a big group and a small group. Before flash photography, the success of the finished photograph was entirely dependent on the available natural light. Once on a very dull day, he didn’t capture much more than a shadow.

When it came to postcards, the choice of subject was wholly driven by its commercial potential. Frank, as Gwen remembers, ‘was looking for anything that would sell. For views, he was looking for pretty bits and anything that would appeal to people. At fetes and flower shows, if he saw a good row of people – he thought well they would probably buy.’

Until 1939, Basil worked in the workroom with another assistant doing all the printing. Frank did the majority of the photography and outdoor work. After the plates for the postcards were washed, Basil rolled them down on big sheets of plate glass and left them to dry. If they did not come off first time, the whole job had to be done again – wetted and left to soak.

The plate glass camera was superseded after the war by the MPP (Micro Precision Products) 5" x 4" technical camera. A heavy camera it required a motorbike or a car to transport it. It was used for weddings and local occasions. But for views, they still used an old plate camera, as the 5" x 4" format didn’t fit on postcards. There were also technical advantages with a long photo lens for landscapes, as it didn’t make the distance look too far off.

A family business

There wasn’t time in the Packers’ lives for anything other than the business. It required all the family members to staff the shop, studio and workroom, while remaining available for commissions. They were always on the alert responsive to local events, whether it was Chipperfield Circus’s elephants passing through the town or capturing Winston Churchill coffin on its way to Bladon. Photos of subjects of topical interest could be shot, printed and placed on a stand in the shop window for sale within a couple of hours.

The Packers employed the young Shadbolt brothers in turn as errand boys. When Will Shadbolt joined up in 1914, he was replaced by his younger brother Jim, aged 10. Jim became fulltime when he left school at 12. He remained with the Packers working in the workroom, developing and printing photos, until he took retirement with lung cancer in 1966. Like his employers, Jim was expected to work through weekends. There was no notion of paid overtime.

For Frank and his wife, Gwen and Basil’s suitors were an unwanted diversion from the business. Gwen ran away to Gretna Green to marry James Walden (above). After the wedding Gwen and James returned home to live with her parents. In an audio interview, Brenda Morris, Jim Shadbolt’s daughter, describes how seething resentment continued in the household with family members avoiding each other and not talking. James, who worked for the county council, died early in his forties in 1956.

After being educated at Bloxham, a local public school, and a period of working for Morris Motors, Basil also joined the business. Brenda Morris describes him as ‘spending his life doing what he was not interested in’. Whenever Basil got a girlfriend, the relationship was quashed by his parents. He finally married Beryl Roberts in 1961 at the age of 55, his parents, however, refused to invite her into their home.

The resourcing of the business changed significantly during the Second World War when Jim Shadbolt and Basil were called up. Gwen, who had previously undertaken all the domestic work, while her mother oversaw the shop, took over Jim and Basil’s roles processing and printing the photos. This required undertaking all the household duties and looking after evacuees during the day, before going upstairs to work in the darkroom. As she recounted to John Simpson in an interview in 1994: ‘I found it very rewarding. I loved making things. Of course, we were very busy with people coming to be photographed. So, we got plenty of work.’ Packer’s photographic services were very much in demand with American servicemen stationed in Chippy, sending pictures home. Gwen recollects: ‘On a Saturday, there was a queue right up from our shop up to the studio. Because you had to go through the house and up the garden to get to the studio. Dad made a notice “to the studio”.’ Photos were printed during weekday evenings so they could be packaged up and collected the following Saturday. The Packers had to be very resourceful sourcing materials that were in short supply because of the war. This included obtaining them from Percy Simms’ studio when it closed and looking out for adverts in photographic papers.

Packer’s legacy

Frank Packer and his love for photography was the driving force between the family business. His enthusiasm for the medium continued to move with the times, he was an early adoptor of the cine camera. In the 1940s, he made home movies of events, such as Victory Day, and of family holidays in the West Country.

After he died in 1967 his children continued the studio until the mid 1970s. Gwen with her interest for photography stoked by the war did a lot of the enlarging and processing after Jim Stadbolt died and ran the shop with Basil taking photographs.

In 1984, the Packer Collection was bought by Oxfordshire Museum Services. Today with almost 3,000 digitalised photos by Frank Packer on the archive’s website, a fantastic visual record of 20th-century Northwest Oxfordshire is readily available to view online.

With thanks to the archivists at Oxfordshire History Centre for their support with this post and for granting permission to reproduce Frank Packer’s photographs. This text draws heavily from two audio recordings:

· Frank Packer, Photographer, 1900-1975: an interview with John Simpson and Basil Packer and Gwen Walden (née Packer), 1994.

· Brenda Morris: an interview with the daughter of Frank Packer’s assistant Jim Shadbolt, October 1993.

Wow - great to catch up with this post today. What a fascinating tale and so rich in family detail. One does admire Packer for all he achieved and I love his dapper look! He was clearly so supported by Mary - and one does feel for Gwen and poor Basil! A brilliant post.