The mystery of the missing son

The fate of John Withers, the shepherd’s eldest son

At every turn, the lives of shepherd Richard Widdows (aka Withers) and his children surprise me. I start out writing one kind of story, then research takes me in an entirely different direction. The intention for this feature was to follow up on What happened to all the women?, my description of the fortunes of Widdows’ seven daughters, with an account of his four sons. I was planning to contrast the way that the daughters went into service far afield, while his sons remained local, working as agricultural labourers in Great Rollright.

However, there was a mystery that I kept bumping up against: what happened to Widdows’ eldest son, John Withers? After the early 1870s, John and his family disappear from UK family history databases. The last record I had for him was the 1871 census when he was working as an agricultural labourer in Great Rollright. My assumption was that he had died. This was shored up by the newspaper reports, written in the last years of Widdows’ life, when the centenarian only mentions three surviving daughters. The truth, however, turned out to be very different, meriting a dedicated piece.

The farmer’s boy

John was the eldest son and third child of Widdows and his first wife, Eliza Penn. Born in 1838, John grew up with his parents and four siblings in a cottage at Fletcher’s Coombe, an isolated valley about a mile north of Great Rollright. John can only have received the most basic of schooling as in the 1851 census, aged 13, he is listed as fully employed as a farmer’s boy.

In 1862, John married Mary Ann Baylis, the daughter of a labourer from Chipping Campden. Mary Ann came to Great Rollright to work as a dairy maid for John and Ann Sargent on neighbouring Coombe Farm. This was the farm that Widdows had first worked on in his youth as a plough boy.

By the time of the 1871 census, John and Mary Ann, aged 33, were living in Berry’s Coombs with their two sons William, five, and Francis, three, along with a lodger, 24-year-old farm servant William Dyer. Berry’s Coombs, later known as Potter’s Coomb, were two cottages adjacent to the church in Great Rollright. Widdows was to move into one of the cottages there in the last few decades of his life. The dwellings were owned by farmer Richard Berry. Presumably, at this time, John was working for Berry as an agricultural labourer.

The whole family, then, vanish entirely, no census returns or death certificates. I scanned the local paper for a news story or tragedy. Had their cottage burned down? It was only then through a lot of online searching that I was able to find a graveside record for Mary Ann Baylis Withers in 1913 in Anderson Bay Cemetery, Dunedin, New Zealand. Then a similar record in the same cemetery for John Withers, who died in 1926. Suddenly I was on an entirely different trail, scanning passenger lists to New Zealand.

Passage to New Zealand

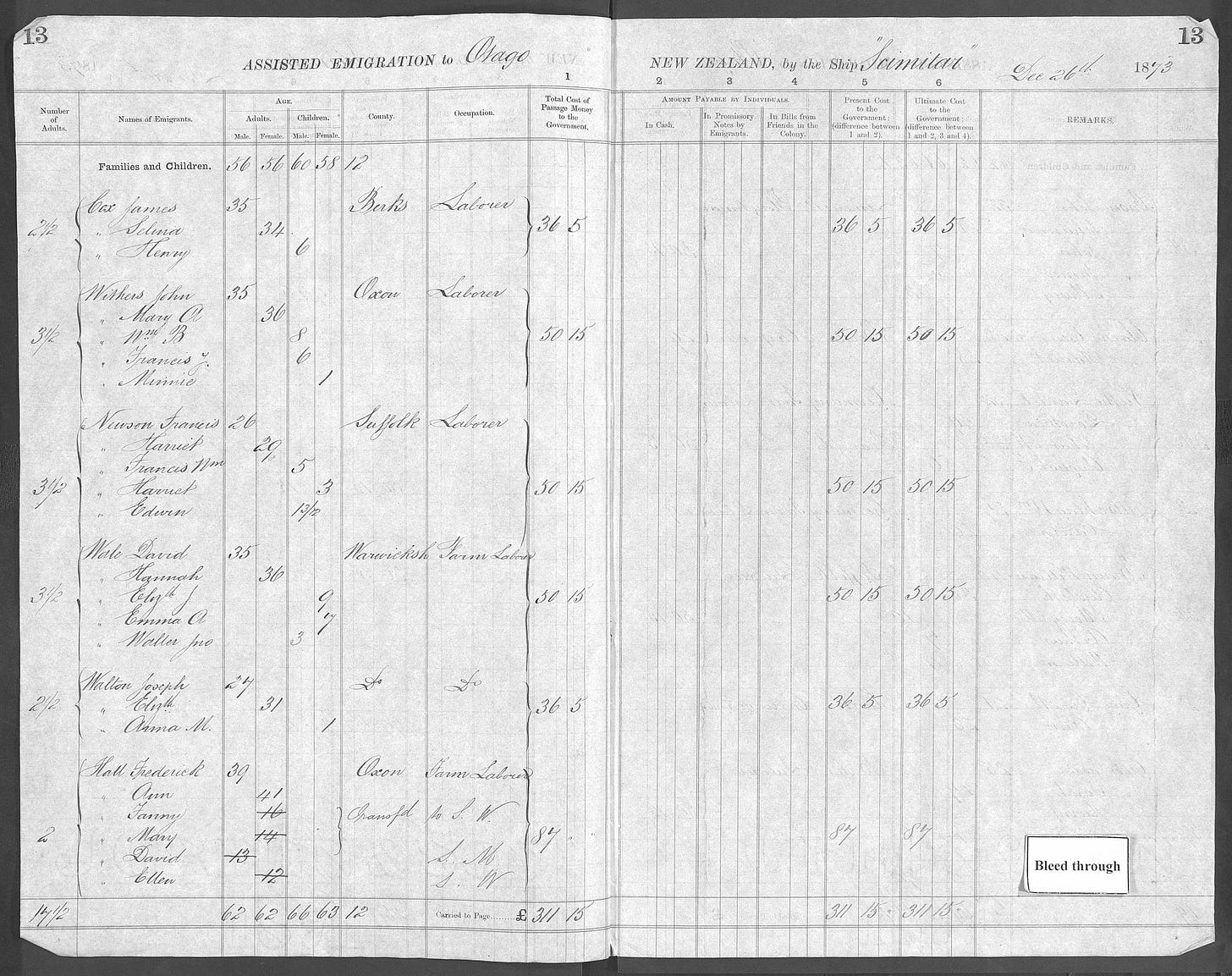

There they all were! John and Mary Ann, and their sons William and Francis, and a new baby Minnie, recorded on a passenger list for assisted emigration to New Zealand. They were logged on a ship that departed from Plymouth on 26 December 1873 and arrived in Port Chalmers, Otago, on New Zealand’s South Island, on 6 March 1874.

In 1870, New Zealand’s Colonial Treasurer, Julius Vogel, had launched a public works and assisted-immigration programme on a massive scale. The ambition was to develop the country’s infrastructure by building railways, roads and bringing in a huge new labour force by funding the passage of thousands of Europeans. This was all financed by massive borrowing from the London stock exchange: the equivalent of billions today. The Withers were a recipient of this programme, along with tens and thousands of agricultural labourers from across the southeast of England and south Midlands, who were struggling to sustain themselves and their families during the Great Agricultural Depression of the early 1870s. On the Withers’ passenger list is recorded the cost to the New Zealand government of every family’s passage. For the Withers, it is logged as £50 15 shillings.

Oxfordshire with its rural poverty and a significant population of struggling agricultural labourers, remote from industrial centres, was made a special target by New Zealand’s immigration campaign. Immigration agent, CR Carter, paid visits to the county to address mass rallies. On 4 November 1873, Carter spoke to 500-600 people assembled in Milton-under-Wychwood; and on 25 November, he spoke to a large crowd of labourers gathered in Charlbury. It seems likely that the Withers’s migration was a direct response to Carter’s activities at the end of 1873. It is most probable that John attended one of these addresses. Both villages are about 10 miles from Great Rollright.

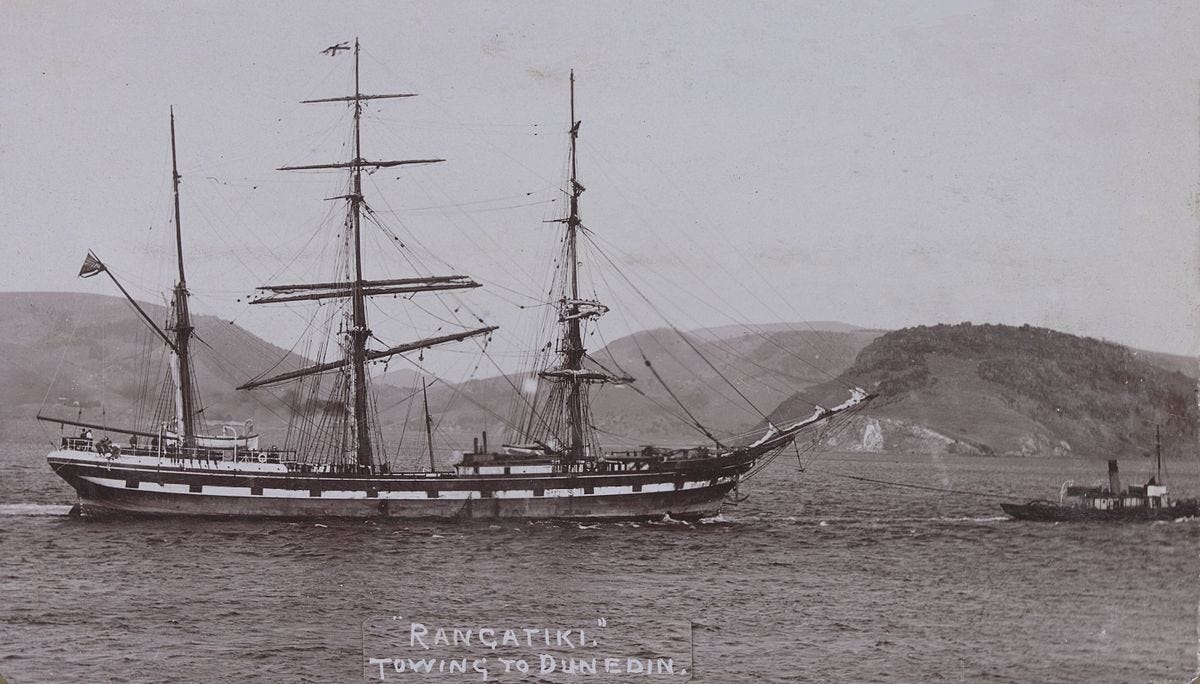

The Withers’s passage was booked on the Scimitar a fast clipper, recently purchased by the New Zealand Shipping Company, which had been overhauled for the journey. It made the journey in record time – 67 days land to land.

Speed, however, was to prove no consolation for such an ill-fated voyage. Leaving London on 24 December 1873, it picked up passengers from Plymouth in disease-ridden barracks. Several individuals contagious with scarlet fever boarded the ship. Scimitar became a ‘floating pest-house’ with 26 people dying from a combination of diseases - scarlet fever, measles and bronchitis. The following sanitary report appeared on the ship’s way bill: ‘Am short of beds and bedding, having repeatedly thrown overboard beds &c. of those dying of scarlatina. The rest has been repeatedly washed and disinfected. Isolation, as far as practicable, has been practised, and a free use made of chloride of lime and Burnet's solution of carbolic acid, with towing overboard and repeated washing [of clothing].’

When the ship sailed into harbour in Port Chalmers, New Zealand, it flew the yellow flag, warning of disease on board. The passengers remained in quarantine for several weeks. The scale of the death toll triggered a Royal Commission of Inquiry and demands for an explanation from the UK Secretary of State for the Colonies. A book by Michael A Beith, No Gravestones in the Ocean: The emigrant ship Scimitar 1873-1874, provides a full account of the ship’s notorious passage. It is no surprise that the ship was subsequently renamed.

Although all five members of the Withers family arrived in New Zealand in March 1874, they were soon to lose their eldest son. Nine-year-old William was buried at Port Chalmers on 10 April 1874.

With only the bare facts of the passage and then births and deaths, it is impossible to get a full sense of the Withers’s subsequent experience of emigration. How easy was it to find themselves housing and employment? Did they overcome the initial trauma of the voyage and start to become part of a new community? The records do tell us that in 1877, Mary Ann gave birth to a third son John in New Zealand. Once they arrived, they did not move far from their port of arrival. Andersons Bay where the couple was finally laid to rest was only 10 miles along the coast from Port Chalmers.

Life back home

The fact that Richard Widdows does not mention a surviving son in his dotage suggests that John was all but lost to him. With no effective means of communication - Widdows was illiterate - he may not have been aware that John was still alive on the other side of the world when he died.

The hardship of rural life meant that Widdows’s three other sons, who remained in Great Rollright, working on the land, all died before their mid 30s: Joseph (b 1846) died aged 15; Soloman (b 1864) died aged 31; and David (b 1867) died aged 24.

Even if it is not apparent how life panned out for John Withers and his family after their arrival in Port Chalmers, it is clear that New Zealand provided John with a significantly longer life than his brothers. He died aged 88 in 1926. His occupation was listed as gardener.

These are really great Helen. I regularly walk past the old shepherd’s headstone in GR churchyard and have wondered about his life. It must be fun (and hard work!) doing the research. Annabel

Very interesting!